Led Zeppelin must have been thinking of Iceland when they wrote these words for the Immigrant Song

"We come from the land of the ice and snow

From the midnight sun, where the hot springs flow"

Winter in Washington, D.C. only remotely resembles winter in real winter country like northern Wisconsin or North Dakota. In the nation’s capital, residents greet the first cold weather in fall by donning their parka’s and bundling up for the cold. Their reality is that the “cold weather” that brings out the parka’s, arrives when the temperature begins hovering in the high forties. That is a warm June morning in North Dakota, and it’s the kind of temperature that brought scantily clad female students on my Wisconsin college campus to soak up the first warm rays of spring in May. Yet, when it comes to cold weather, Washingtonians’ take no chances.

A Washington winter becomes even more difficult to comprehend when they mention the “s” word on The Weather Channel. Say “snow” to a Washingtonian and even the most stalwart, money-draped Republican lobbyist on K Street starts to shake in his boots. It’s because snow can bring this city to its knees. Even a little bit of snow can do it because nobody knows how to drive in the stuff. I found that out the first time they issued a “snow emergency” here.

No matter where else I have lived in the United States, when The Weather Channel flashes up a red severe weather alert on your screen, you could expect a severe thunderstorm or a tornado or a hurricane to be nearby. The Weather Channel on a Saturday night was flashing a red screen when I turned on the television in early evening. I looked at the calendar and it said January. I wondered if a freak thunderstorm was headed toward town despite the temperature being in the high twenties. Reading the screen, I learned that we were under a winter storm “warning” that called for “up to four inches of snow.” I had to reread the screen several times to make sure that I wasn’t experiencing a flashback from some bad acid in college. Still, each time I read the screen; it said the “warning” was for up to four inches of snow.

In northern Wisconsin, we looked at four inches of snow as a good start. In North Dakota, if four inches of snow didn’t blow by you sideways each hour, then it really was not a snowstorm. In Washington, though, four inches of snow was a warning that the end of the earth may be near. Because this was Saturday night, it was a regular night for grocery shopping and after rereading the red screen several more times I made my usual weekly trek to Safeway.

Pandemonium reigned in the grocery store. Everyone was in a frenzied search for “essentials” because of the incoming “up to four inches of snow.” They wiped toilet paper off the shelves, and all the milk and bottled water was gone. Anything resembling bread was going fast. Almost anything any shopper discussed as I struggled for available space in the aisles was the incoming snow. I stood in line to check out for more than an hour because each of the six open checkout lines averaged twenty-one people deep. Nobody in suburban Virginia was going to take chances with this four-inch snow emergency.

Driving home from my office the day before, I noticed that a nearby discount gasoline station had dropped their price for unleaded by four cents. The gas gauge in my car was hovering about one-eighth full as I pulled out onto Franconia Road and I thought of the gas station. Pulling into their lot, I found it, like Safeway, jammed with long lines of people. I wondered if everyone but I had heard about something horrific happening to the world gasoline supply. Instead, the lines at the gasoline station had formed because everyone had seen that red screen on The Weather Channel.

Just like being caught short with no toilet paper in the house, nobody was taking a chance with no gasoline if this “storm” hit like they heard it would.

The woman in the car ahead of me in the line looked nervous and was smoking a cigarette. I walked up to her and asked if she knew why so many people were waiting in line. She took a long drag on her cigarette and said, “didn’t you hear, there is a snowstorm coming?”

I asked how much gasoline she had in her tank. “I’m down to almost a half tank.”

“Why are you worried about snow if you have more than a half-tank of gas?”

She said, “If we get the snow they say we are supposed to get, the delivery trucks won’t be able to get through to the stations. I’m just not taking any chances.”

I thought about her concern for a few moments, and then had to ask what to me was a basic question. “Did it ever occur to you that if there’s so much snow from this storm that it blocks the roads for the delivery trucks, you won’t be doing any driving anyway?”

Logic seemed to leave her behind when I asked my question. “You just don’t understand, do you?” she said as the car ahead of her pulled forward to get some fuel before the impending storm blocked all the roads.

True to the prediction, we received almost four inches of snow that night. Fluffy, dry snow that in North Dakota would have been in South Dakota with the next wind gust an hour later. In the nation’s Capital, however, it was a major traffic disrupting event. Disrupting all but those few of us who grew up in winter country where we see four inches of snow as a nuisance.

Venturing out on the back streets of suburban Virginia that morning, my objective was to find the Sunday edition of the Washington Post. My interest in the Sunday paper is twofold. I like to read the opinion section on Sunday so I can keep track of what the Repugnicans are thinking. Most important, I read the Sunday paper to get the travel section. There is always the chance that if the Repugnicans come up with something horrific, an advertisement in the travel section for cheap airfare might give me the excuse to be out of town when they put the Republican plan in place.

Driving on Franconia Road on “Snow Emergency” Sunday was an education. The most apparent education was that very few people know how to drive on snow and even fewer know how to stop on it. Dodging and darting among cars sliding out of control on patches of snow, I luckily found a newspaper machine and returned home to see what they had been up to and to find out where I needed to go to escape.

A verse in one of Jimmy Buffett’s many hit songs states, “lately, newspaper mention cheap airfare, I’ve gotta fly to St. Somewhere . . .” Given Buffett’s proclivity for warmer climates, his notion of St. Somewhere must lay at a latitude considerably south of the Tropic of Cancer. That verse flowed into my mind as I scanned the travel section and saw many travel bargains to warm places like Cozumel, St. Lucia, Acapulco, and Hawaii. Yet, on this snowy day, I saw an advertisement by Icelandair offering surprisingly cheap airfare and hotel packages to Iceland. Their advertisement featured two Atlantic Puffins urging Washingtonians to “come up and see us sometime.” The fares they were offering to Iceland and most of the airline’s European destinations would make anyone with even a dash of interest in Europe want to leave town and leave soon. In April? Why would anyone in their right mind want to fly to the verge of the Arctic at the end of winter just to hang out for a few days? It was a question we asked ourselves all afternoon until I called the airline.

Formerly known as the "Hippie Airline" to Europe, Icelandair no longer has hippie airfares although Business Class seats aren't as outrageous as they are on American Airlines!Icelandair’s flight, a nearly packed 757, was scheduled to blast off from Baltimore airport at eight in the evening, but the departure signs told a different story. We would be an hour late departing because the inbound equipment from Iceland would be an hour late arriving. Information on the status of the delayed flight was scant, but unwillingness by Icelandair to be forthcoming with information at the gate was in line with my original experience buying a ticket.

Curled up in a jet at 35,000 feet above the frosty North Atlantic in late March, and about five hours after leaving the Baltimore airport, the pilot announced that it was time to prepare for our arrival in Iceland; we were only thirty minutes from landing.

Stiff-legged, and with only a few hours of fitful sleep en route, we extracted ourselves from the plane and moved past each gate in the airport. I once told myself that I had been traveling too much when I walked through Continental Airline’s South Concourse in Houston and realized that I had been in every airport named on a departure gate display panel at that hour. Today in Iceland I could not say that. Not once.

Fifty years ago, Icelandair was the “hippy” airline of choice to Europe because it was the cheapest alternative from the States over the pond. Many think it still is today. The departures this morning were to places like London, Stockholm, Oslo, Luxembourg, Copenhagen, and Paris. All were new airports for me at the time. All new adventures waiting for some time in the future and at really cheap airfare from Washington.

We exchanged money at the Landisbankki in the airport. Although this is the National Bank of Iceland, and the bank that prints Iceland’s krona, they charged us a $300 krona commission for each exchange. This turned out to be a mild precursor of future events.

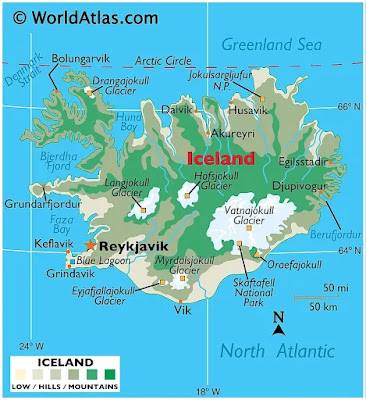

Although a doctor would have probably declared me brain dead from sleep deprivation, I took in the striking scenery as a bus whisked us thirty miles to the city. From the airport we passed through an endless procession of starkly barren lava flows mingled with lush patches of Arctic tundra. Occasionally on the distant skyline we would see a small volcano. Steam vented from nearby geysers, and the North Atlantic was pounding relentlessly on the basaltic shore. To the north we saw glaciers, and as we approached the capital, majestic Mount Esja watched over the thousands of Reykjavik residents from the opposite shore of the Faxafloi. Everything I saw told me that I was either in Anchorage or Nome or both. The only real difference, other than the slight variation in the accent of the residents, was that I could not read the road signs.

Our hotel, like the bus we drove to it in, was owned by Icelandair. In quality it was like a Sheraton but the room was overpriced for the size of the room. Checking into our postage-stamp sized home for the next three days, the weight of not much sleep in the last few hours was taking its toll. Still, the excitement of a new place caused an adrenalin rush to override the need to sleep. A hillside near the hotel supported the growth of stunted coniferous trees, so I walked toward them hoping to find birds. My chances were good that any bird I saw would be a new species because this was my first time in Europe. Disappointment came over me when I heard the familiar squeaky call of a European Starling. It was a true European bird, and that couldn’t be argued; I had hoped for a little better-quality bird for the first mark on my European bird list. An unfamiliar flute-like voice deeper in the stunted trees drew me toward it. Its character and its cadence told me it was some species of thrush. The only European thrush I had seen before was a Fieldfare that showed up one November in northern Minnesota. That bird never spoke and I had no idea about the sound of a Fieldfare voice.

The bird remained hidden from view as it sang incessantly from somewhere in those trees. There were several males of whatever species this was, singing from the trees and all of them remaining stealthily out of view. Suddenly a male popped into the air and flew over me. It was large and American Robin-like and flashed red underneath. This was one of two species, although identification on the wing was problematic. He chose to land at the top of one of the stunted pine trees and continued to sing his ethereal song. It was a Redwing, a common thrush throughout Europe. I watched the bird for fifteen minutes and listened. I returned to the hillside an hour later and could not hear a single Redwing voice.

I was elated that Redwing was my first European bird! Now after 36 trips to Europe they seem as common as American Robin does back in the United StatesOur rental car arrived in midmorning and despite a severe lack of sleep, we left to explore Reykjavik. We stopped at the Iceland Tourist Bureau office at the edge of the city where the selection of pamphlets on area attractions was almost overwhelming. Also present were several system schedules for airlines. Another of my vicarious travel methods is reading airline schedules. When I find that an airline flies to a city that is not familiar to me, I bring out the atlas to find it. I look at the landscape and try to imagine what the river might look like if they show one on the map. I try to envision what the mountains nearby are like. Are they barren? Are they heavily forested? With Central American mountains, are they denuding them?

Unable to resist collecting them, I picked up an Icelandair schedule. Next to it was a schedule for Greenland Air. Its cover contained the title in Greenlandic, English, and probably in Danish. Whatever language was the third one, they spelled flight schedules “Fartplan.” Though I had no intention of flying the airline, I could not resist a schedule that calls their flights farts.

Exploring downtown Reykjavik gave us a mixture of our first exposure to European architecture mingled with Arctic architecture. My time in the Arctic had taught me that the most common form that a building occupies is a cube. That form may be the most efficient for holding in heat in the long, cold, winter months. Whatever the reason, cubical buildings are an instant hint that you are somewhere cold. In downtown Reykjavik, they juxtaposed buildings in cubes with Gothic-looking buildings and some that could easily line the Champs Elysees.

A small street map given to us by the tourist office helped orienting on the streets of Reykjavik. It contained great detail, showing the location of buildings and areas of interest. Its only problem was that they wrote each word in Icelandic. Having no comprehension of the language, we made up our own pronunciations of the street and building names. Luckily, no Icelanders heard us butchering their language as we wound our way through the streets.

Reykjavik is a beautiful city to explore with more bookstores per block than any other city I have visited. Just be aware that all the street signs are in Icelandic and that is a very tough language to master!We followed the map as best we could and eventually found Lake Tjorn near the city center. Although we were there in April, the lake was open through the constant paddling of ducks and geese and swans of several European species. Lake Tjorn kept our attention for thirty minutes before we went off farther to explore. Traveling next to the harbor, we hoped to find some gulls, but instead found Northern Fulmar. They were everywhere in the harbor, flying around like gulls on the Delaware shore. All my experience with this species was either well out at sea off the east or west coast, or at remote nesting colonies in Alaska. I had never imagined them as harbor birds but they seemed to fill that role in Iceland. Also, littering the harbor’s waters, was an almost endless flock of Common Eider. The numbers of this sea duck resting and feeding on the Reykjavik harbor gave new meaning to the word “common” in their name.

Common Eiders are insanely abundant in the harbor at Reykjavik and on ocean waters around the country. Photo by Bruce MacTavishHunger drove us away from birds and in search of food. Our travel guide recommended a restaurant on Tryggvagata Street as a good place for a quick meal. It was packed with Icelanders having lunch, and the smoke hanging in the air told us that Icelanders not only liked this restaurant but lingered there savoring their food while befouling the air. Our forty-dollar lunch for two included fish and chips and two soft drinks. Its cost convinced me even more that I was back in Alaska.

Thingvellir National Park lies about twenty miles east of the city. Our travel book suggested this would be a good place to observe the tundra landscape, and it provided opportunities for seeing some of the limited wildlife that does not migrate south during the harsh Icelandic winter. Finding our way there was easy using our personalized bastardization of the pronunciation of most Icelandic words on road signs.

The road to the National Park was practically lacking other traffic that made it easier and safer to stop often to view the magnificent glacial vistas. No matter where we looked, nature had provided a photo opportunity. I am always amazed in National Parks in the United States where, as you travel through crippling beautiful scenery, someone in the highway department saw fit to put up a sign alerting you to a “scenic view - 500 feet” - as if you needed to be reminded that the countryside was exquisite. There were no such signs on this Icelandic highway today, although it could have supported many.

No photo can adequately capture the stunning beauty of the Iceland landscape. Its a place that has to be seen to fully appreciateAlthough only three weeks into the new spring, and at a latitude equal to Anchorage, there was considerable sunlight remaining at seven in the evening. Our travel guide recommended several places downtown for dinner but we were zombie-like from a lack of sleep that I no longer wanted to take chances driving on unfamiliar streets after dark. Instead, we chose the hotel restaurant for our first Icelandic dinner. Several signs in the elevator and elsewhere in the hotel promoted the buffet dinner and we followed the advice of the signs. After all, buffets are usually a cheap alternative with much food.

There was a lot of food. Mainly a lot of fish. They baked it, boiled it, broiled it, barbecued it, fried it, and served it raw. It included salmon, haddock, whitefish, herring, cod, and several other kinds that I didn’t recognize. Entire hips of lamb smothered another section of the buffet line before taking us back to more fish. Their vegetables were mainly tomatoes, carrots, and potatoes. There was nothing elegant or exotic. There was an abundance of food here and we filled our plates and went back for more. I had a liter of some Dutch beer. Then we got our bill that was the U.S. equivalent of $85 for two at a buffet. The meal was actually only $75; the liter of beer was ten dollars. I had read that the Icelandic government placed a remarkably high tax on alcohol, probably to discourage consumption during the long Arctic winter. Their plan worked perfectly for me because this was the only beer on the trip.

Sleep came easy and hard that night since it had been so fleeting the night before. When the six o’clock wakeup call came, it was still one o’clock on our body clocks. We lay there contemplating more sleep until today’s plan bounced off several deadened neurons. Our plan for today was to travel north to the Snaefellsnes Peninsula at the northwestern most point of the island. The highway maps showed the route passing along the edges of several fjords, and near several glaciers. Being of Nordic ancestry and from the land where fjords are a common part of the landscape I shook off the desire to go back to sleep and got ready for the day.

Breakfast this morning was included in the hotel rate. Walking downstairs to the restaurant, I started to imagine what my first real Nordic breakfast would be like. I was anticipating something exotic like the salmon and caviar that they once served to me as an authentic “Scandinavian breakfast” at a violently expensive Minneapolis hotel. On entering the restaurant, the restaurateur in Minneapolis had apparently never visited Scandinavia before making their breakfast menu. Here in Iceland a real Scandinavian breakfast was tables full of granola or cheerios with pitchers full of milk and yogurt. On another table were mounds of Danish, sliced tomatoes, sliced cucumbers, stacks of sandwich meats, stacks and stacks of sliced cheeses, and a variety of what looked like dinner rolls. That was it. The nearest salmon was swimming in Reykjavik Harbor. There wasn’t even a hint of caviar. I told myself that I needed to write to the restaurant in Minneapolis when I got back and tell them they had done it all wrong.

As I was enjoying my granola and yogurt, I saw a man at the adjoining table return from the buffet with a plate holding three Danish, and stacks of sliced cucumbers, tomatoes, and sliced cheeses. He took one Danish and laid a slice of cheese on it. A slice of tomato was laid on the cheese and a slice of cucumber was placed on the tomato. For a garnish he used another slice of cheese for the top. He finished the first Danish, took a large drink of coffee, then started to layer the next Danish to replicate the first one.

I thought Scandinavian breakfasts were all about salmon and caviar until I watched Icelanders piling vegetables on top of vegetables on a Danish and washing it down with coffee!I sat in awe through the second Danish. For his final one, he wasn’t too concerned about the order of layering. Two slices of cheese topped his concoction. It was almost thicker than a Big Mac. Living by the motto of “when in Rome . . .” while traveling, I returned to the buffet table and mimicked the man at the next table. Never in my wildest dreams had I thought of eating a Danish with vegetables and cheese as a garnish.

We stayed near the coast as we drove north from Reykjavik. Everywhere we looked on the ocean’s surface, we saw bobbing the white, black, and green bodies of tens of thousands of Common Eider. Over them flew a constant procession of Northern Fulmar. At one rocky outcropping we saw adult fulmars landing precariously on ledges for what I assumed was nest building. We came to Hvalfjordur that our travel guide said was Icelandic for “whale fjord.” In August up to seventeen species of whales can be found on the fjord. Today we had to settle for endless sheets of Common Eider.

Few people live along the ocean north of Reykjavik. In the United States, areas similar to what we were traveling through would have been littered and defiled by homes, and second homes, and gas stations, and strip malls. Any outlet to suck money from the people traveling by. In Iceland, there were no homes. Instead, there was endless, boundless beauty.

Too many vistas required us to stop driving and explore. Too many interesting landscapes required extra time to try to understand what the glacier did as it gouged out pieces of earth here and spit those pieces out there. We were moving north at a snail’s pace. By eleven that morning we were still more than two hours from the base of the peninsula. The clear morning sky had become obscured by clouds and light snow started to fall. This much snow in Washington D.C would have been more than enough reason to declare a snow emergency. Along this isolated road in Iceland, the snow only accentuated the beauty of a landscape already abundant with beauty.

By noon we were still a great distance from our destination and despite the veggie Danish for breakfast, we were starting to get hungry. The village of Akranes loomed in the distance. Our travel book listed several good restaurants there and mentioned a ferry that ran four times a day to Reykjavik. Instead of continuing north to the peninsula, we ended our northward trek at Arkanes.

Only 26 miles north of Reykjavik by ferry, the village of Arkanes is a must see on any explorer's visit to IcelandAs we entered the village, it was apparent that cubic architecture was the norm, and that fishing was the main industry. We followed the coastline through the village and found the requisite flocks of eiders and endless flocks of gulls. Our guide recommended a good restaurant near the beach for “inexpensive” lunches. Our forty-dollar plates of halibut and haddock were about normal, I guess, for an inexpensive Icelandic lunch.

We learned at the ferry office that the next sailing was at midafternoon so before catching a ride back to the city we explored more of Arkanes. Near some fish packing plants, we found a small flock of Northern Fulmar patrolling the shore maybe ten feet from us. The Icelandic word for fulmar means “foul gull.” The foul part is a reference to their tendency to ejaculate their stomach contents as a defense mechanism.

Returning to Reykjavik we spent the remainder of the day exploring downtown. Shops selling woolens outnumbered all other clothing stores. Maybe it has something to do with the long winters? We searched several stores hoping to find the perfect wool sweater. Most of the wool products in most of the stores were marketed as made from “virgin wool.” I have often wondered how the manufacturers could attest to knowing that each sheep was a virgin when it gave up its wool while being sheared. That would be exceedingly difficult to determine in Wyoming. found a bookstore between a couple woolen shops and went inside to explore. Unlike the United States where NASCAR racing and Sunday afternoon and Monday night football is the national obsession, in Iceland the narcotic of choice is books. An important part of the history of the country is the “sagas” written more than five hundred years ago. Iceland, unlike the United States, enjoys one hundred percent literacy. Many of those well-read Icelanders learned how to read from the sagas.

During our time in Reykjavik I was tempted to ask someone if smiling were illegal because few Icelanders did. I found a book in this bookstore titled “A Xenophobe’s Guide to Understanding Icelanders.” I purchased the book and read it. It explained that being quiet and reserved is just the norm for the Icelandic people. Their quiet and reserved nature contributes to their not understanding some American’s like me who does nothing but ask questions.

Still in shock from last evening’s $85 buffet dinner, we sought out the downtown area that night hoping to find a less expensive place for dinner. Our travel guide mentioned a Thai restaurant called “Thailandi” in the downtown area. We found it easily because it had the only Coca-Cola sign in Thai script in all of Reykjavik. After enjoying chicken and shrimp curry for one-quarter the cost of last night’s dinner, we went to bed and found sleep followed within seconds of our heads hitting the pillow.

The landscape we passed through during our bus ride to the city was a fuzzy memory of our first morning. I vaguely remembered the tundra, and I thought there were geysers on the horizon, yet my mental condition that morning could have made them a dream. Something we read earlier mentioned a huge nesting colony of seabirds near the southwest corner of the island. With another Scandinavian breakfast of veggie Danish to fortify us, we left Reykjavik to find out what we saw the first morning.

The world famous Blue Lagoon is a tourist trap of gargantuan proportionsAlmost any tourist information brochure printed in Iceland devotes some space to touting the “Blue Lagoon” as a place that everyone must visit. Several tourist tours to see the “authentic” Iceland take visitors to the Blue Lagoon. We turned south off the main road and drove to the lagoon. It is a thermal hot spring like the fountain of youth that Ponce de Leon tromped all over Florida trying to find. It was also the only major tourist trap that we saw in western Iceland. Tour buses filled its parking lot and the buses were disgorging Americans. We continued south. Americans are the last thing I want to see when I leave the United States.

The tiny village of Grandivik sits as a sentinel on the barren, windswept south coast of Iceland. Any storm racing north with the Gulf Stream will collide with Grandivik first. Any storm from the Arctic moving south over Iceland leaves its final punch in this village. It’s a village secluded among barren lava flows.

A volcano near Grandivik, Iceland, began erupting in January 2024. I hope it has its sights set on the Cod Liver Oil factory in that town! Photo by BloombergWe watched fishermen making final preparations before heading out to sea. Groceries were being stowed in the galleys while deckhands curled and uncurled fishing nets. We could see a boat captain in the wheelhouse making final plans. The next generation of Icelandic fishermen was standing by the boats wondering when they would be allowed to go to sea like every other relative and ancestor in their family had done. We watched one boat leave the harbor en route to rich fishing grounds hidden by the waves. Iceland’s most important export is cod. A versatile fish whose liver oil my mother used to force feed me “because it’s good for you” when I was a child. It dawned on me that the first time I had ever heard of Iceland was when I read the label on a bottle of that vile oil I came to loathe as a child. I looked around Grandivik hoping there was a cod liver oil manufacturing plant. If so, I wanted to have a chat with the manager about maybe putting some flavor additive in the next batch of his product shipped to Wisconsin.

We left Grandivik when the boat we watched leave the harbor was just a speck on the southern horizon. North of the village we found a road signed for a place called Reykjanesvti. It didn’t show as a settlement on our map, and after two hours of searching we didn’t see anything with that name on it. Maybe the tourist commission puts up signs for Reykjanesvti to fool the tourists?

The on-again, off-again asphalt and gravel road leading to the nonexistent place called Reykjanesvti passed through extensive lava flows. Occasionally we found a wetland set in tundra vegetation. Several species of ducks floated on the ponds doing their courtship displays telling us that the real spring wasn’t far away. Reaching the end of the road without finding what we set out to find, we could see a lighthouse in the distance and worked our way to it. At the edge of the ocean beneath the lighthouse were several rocky outcroppings that geomorphologists call sea stacks. Each stack was crawling with Black-legged Kittiwakes actively and noisily defending territories and waiting for a mate.

Eldey Island, a sea stack off the southwest coast of Iceland is an important nesting site for seabirds. It used to support nesting Great Auk, but the Auk is now extinct and the last one died on this islandOffshore from the stacks and almost on the horizon was Eldey Island. Through binoculars it looked bleak and barren like any other volcanic island in the Arctic. However, for the natural world, Eldey Island was far from typical.

The Great Auk was a large, flightless, cousin of the Atlantic Puffin. In some ways the Auk was to the Arctic what Penguins are to the Antarctic. They laid one egg a year and because they were flightless, Auks nested on isolated islands where predators were less likely to rob their nests or kill the newly hatched young. Their plan for survival worked masterfully until sailors and other explorers in the Arctic discovered the birds, discovered that they could not fly, and discovered that their flesh was a welcomed relief from a constant diet of fish.

"And the sailor who clubbed the last Auk thought of nothing at all."... Aldo Leopold. Illustration by John James AudubonAuks’ were systematically killed at nesting colonies throughout the Arctic. Their inability to fly made them easy prey for anyone with a club in their hand. Looking across the blue-gray North Atlantic at Eldey Island, I remembered a quote from Aldo Leopold’s classic work “A Sand County Almanac.” Citing an incident on Eldey Island in 1844, Leopold wrote “and the sailor who clubbed the last Auk thought of nothing at all.” I was there 152 years after that last Auk drew its last breath. Unlike the unthinking sailor in Leopold’s book, I couldn’t stop thinking about what happens when humans try to tame the earth. In the end, the earth always wins the race. Still, humans do despicable things to the earth before she comes back to reclaim what we have stolen from her.

Today, Eldey Island no longer supports the great alcid but it is home to the largest nesting colony of Northern Gannet in the world. Looking at the place where the last auk died, I hoped I was witnessing a place where a scene occurred that will never happen again.

Stopping for gasoline at a station near the airport, we decided to check out a nearby grocery store to compare its prices to those in Virginia. Many of the staple foods were comparable in price but there the difference’s end. Alcohol was astronomically expensive, and we found a ten ounce of hamburger for the equivalent of eight U.S. dollars per pound. No wonder so many dinner dishes are prepared with fish.

I commented to the woman checking out our purchases that she spoke the clearest English we had heard since arriving in Iceland. She thanked me for the comment and said that she learned English while an exchange student in the United States. I asked where she had lived in the states, and she said, “in northern Virginia.”

I asked where in northern Virginia and she said “Alexandria.” I asked her which high school she attended while she was living here and almost fell over when she said the name of the high school five blocks from my home.

We returned our rental car to the Hertz outlet several hours before taking the bus to the airport for our return flight to the United States. Examining the rental car receipt I noticed a block for “parking ticket” and something struck me. During our first afternoon in Reykjavik, I noticed a small plastic envelope under the windshield when we returned to our car from lunch. I hadn’t noticed the envelope before we parked in what I assumed was a free municipal lot. Eventually I removed the piece of paper inside the plastic and saw that everything was written in Icelandic except the license number of the car. There was also a symbol for Icelandic Krona and the number 850 beside it. I had every intention of asking someone if that were a parking ticket although it slipped my mind until I read the rental receipt. Of course, I didn’t confess to the people at Hertz that I was skipping out on a parking ticket.

We caught the afternoon Flybus for our reluctant return to the airport. Leaving the hotel parking lot, we had one last breathtaking view of Mount Esja with its fresh layer of snow half the distance down its side. Two church steeples were perfectly aligned with the mountain backdrop that completed an almost indescribable view.

Our return flight to Baltimore was an hour late departing because our plane was an hour late arriving from Oslo. Eventually I accepted the fact that Iceland is an island, and Icelandair is an island airline, so it stood to reason that they operated their schedule on island time.

I have returned to Iceland only once since that first trip in the mid-1990s. The second time was in 2015 enroute from New York Kennedy to Stockholm, Sweden. The least expensive way to get to Copenhagen was on venerable Icelandair and the airline deposited us in Keflevik airport on time at 6:00 a.m. Sadly, we departed for Copenhagen at 7:30 so we barely had time to clear immigration before we were back in the air.

Our route of flight took us over the stunningly beautiful ice fields of southeast Iceland that created an instant case of wanderlust and made us want to see the southeast ice fields in person.

That opportunity presented itself when we found a Norwegian Cruise Line cruise leaving Reykjavik for New York City. Before its trek south, the original itinerary had us making a complete circumnavigation of Iceland with a one-day stop in a town in southeast Iceland not far from the gigantic ice field we saw from the air. Full of anticipation we booked the cruise only to discover, after we had made full non-refundable payment on it, that Norwegian changed the itinerary and was no longer circumnavigating Iceland. In fact, we would not even be close to circumnavigation!

Instead, we spend 3 full days visiting small towns on the northwest and north coasts of Iceland. The new itinerary looks like this:

|

|

Revised

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stopping in Husavik is one positive part of the change because Husavik is the “Whale Watching Capital of Iceland.” We should see lots of Humpbacked and other whales there. Twenty-three species of whale have been confirmed in Iceland so anything is possible. Atlantic Puffin is abundant in Icelandic waters as are other seabirds like Northern Fulmar and Arctic Tern. Atlantic Puffin are actively hunted in Iceland and their flesh is considered a delicacy. I will not, however, be eating any!

Atlantic Puffin is ridiculously common on nesting islands off the coast of Iceland. By Charles J. Sharp - Own work, from Sharp Photography, sharpphotography.co.uk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106949397

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment